ALBUMS

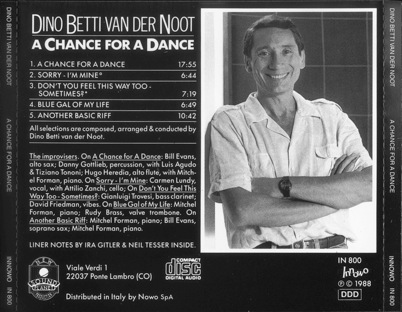

A CHANCE FOR A DANCE DINO BETTI VAN DER NOOT

1 A Chance for A Dance 17:55

2 Sorry – I’m Mine° 6:44

3 Don’t You Feel This Way Too – Sometimes? * 7:19

4 Blue Gal of My Life 6:49

5 Another Basic Riff 10:42

Total playing time 49:29

All selections are composed, arranged and conducted by Dino Betti van der Noot.

Jacket Artwork by Titti Fabiani.

The Improvisers. Luis Agudo, Rudy Brass, Bill Evans, Mitchel Forman, David Friedman, Danny Gottlieb, Hugo Heredia, Carmen Lundy, Tiziano Tononi, Gianluigi Trovesi, Attilio Zanchi.

The Orchestra. Mark Curry, Sergio Fanni, Mike Burke, Luigi Tisserant, trumpets & flugelhorns; Rudy Brass, trumpet, flugelhorn & valve trombone; Luca Bonvini, Ron Burton, trombones; Dana Hughes, bass trombone; Fiorenzo Gualandres, bass trombone & tuba; Hugo Heredia, Bill Evans, Gianluigi Trovesi, Rino Lagona, Marco Visconti, Peppino De Mico, reeds & flutes; Mitchel Forman, Steinway grand piano; David Friedman, vibes (* only); Gianni Faré, vibes (all selections except *); Mark Egan, electric bass; Danny Gottlieb, drums & percussion; Luis Agudo, Tiziano Tononi, percussion; Carmen Lundy, vocal (° only).

Milan, 1987-88.

“I love the rhythm – one of the reasons I love jazz is the rhythm – but I have spent some years to free myself from the rhythm”. Dino Betti van der Noot sits over breakfast rolls at the Rosetta Hotel in Perugia, Italy. “I experimented with different time signatures and finally found out that the simplest ones are perfect, as long as you make use of them as, oh, railways, rail tracks”. In other words, the time-feel must be a guide, a phisical, visible presence – “but at some point, the music – the melody – must actually be free from this time”.

That concept is bound up in the title of this collection. It’s just a matter of giving the music “a chance to dance”. And the music of Dino Betti van der Noot, in its latest phase of development, dances with grace and logic, power and delicacy: Grand strides throughout. His is quite possibly the most invigorating and challenging approach to large-ensemble writing in jazz today, drawing on the lesson of the past, processing the present, and helping to define the future of the big band idiom.

The past? As others pointed out, Dino shares with the Ellington legacy a passion for customizing his compositions to the individualized talents of his orchestra. (In fact, this was probably the most vital of Ellington’s artistic realizations, since so many enduring pieces – from The Mooche through Crescendo And Diminuendo in Blue – were based upon it.) When Dino prepares a piece, he creates a frame for the particular quality of the projected soloist – be it the fleet power of a Bill Evans, the cool passion of a Mitchel Forman, or the husky cry of a Carmen Lundy. Explaining his facility with such a wide palette of instrumental sounds, Dino shrugs: “I played many instruments in my life – all of them poorly”. (All, I would argue, except one.)

As for present, this album is the fourth that Dino has recorded, but it can more accurately be considered the latest chapter in what is already a rich and remarkable body of work. Most obviously, Dino reveals in an impressive range of color and imagery. He programmatically leads his listeners through deserts and up mountains; he navigates exhilaration and despair, conjuring sharp and pure visual images from his wide palette of sounds. But despite his acumen as a total painter – and make no mistake, Dino is a direct descendant of Ellington, via Thad Jones and Toshiko Akiyoshi, in the continuing explosion of timbral possibilities – the freshness of his sound and the originality of his music really lie elsewhere.

Specifically, it is the underlying draftmanship, along with a noteworthy sense of scale and form, that mark Dino’s writing. He works on large canvasses; he needs to, because for the most part, he deals with large musical issues (although he fills these canvasses with finely-wrought detail). The title composition of this album supplies the perfect example. The longest of his works – “It was born little by little on the piano,” says Dino, who often refers to his pieces in antropomorphic terms – A Chance for A Dance raises and solves a variety of artistic problems. In it, Dino wrestles with balance and structure, criss-crossing tonalities, the concurrent development of multiple themes, and fitting the individual (the soloist) into the now disciplined, now anarchic constraints of society (the orchestra). Referring to its multiple sections and recurrent theme, Dino admits, “I didn’t think about structure, but I’m happy with the structure that resulted. I think you must have a certain kind of classical background to automatically choose this structure. Each theme brings to the composition a different atmosphere”.

At this point in such an essay, the writer usually feels compelled to point out that such clinical concerns should not deter the musically unschooled listener from just “digging in” to enjoy the music. I won’t insult your intelligence by doing this. For although specific analytical thoughts need not be the constant companions of any listener or critic, they are quite naturally inspired by most music worth listening to more than once. In fact, such concerns are at the heart of Dino Betti van der Noot’s compositional process, and so it can come as no surprise that his music demands intellectual, as well as emotional, responses.

Cool and quietly elegant in person, Dino is efficient and directed in speech and thought; it is his prolific output, and his relentless attention to detail, that offer telltale proof of his hyper-energetic nature. And yet, he says, “I am not pushing. If I were obliged to make music, the results would not be so good. Normally, I don’t even plan to make an album. I am exploring certain possibilities to make music, and when I have enough I make an album”.

Dino’s late-1987 performance in New York, where he conducted a hand-picked group of New York musicians, received a mostly favorable notice in the New York Times: The review did, however, suggest that he would be well served to go beyond his own material and utilize his arranging skills on other compositions from the recognizably great jazz composers. It’s no surprise, given his quest for perfection, that Dino gave this comment a great deal of consideration; but now, he muses, “I don’t think I will change a thing. Because actually, I am not arranging; I am composing”.

For Dino, they are one and the same – medium and message, substance and style – and it is the success of this twinning that, more than anything else, sets him apart from the other jazz composers of his time.

Neil Tesser

Egan and Gotttlieb, two of the mainstays of the Gil Evans orchestra, both hold Betti van der Noot in high regard. “I find Dino’s music to be very experimental and challenging,” says Egan. “I’m glad I have had the experience of Gil Evans so I could communicate through Dino’s music as well. Dino’s music is very challenging for the bass. I also enjoyed playing with the other musicians on the record”.

Gottlieb feels that “Dino’s music is coming from a direction that hits close to home. Gil’s influence is in here. It is interesting, unique writing that’s not predictable. There are not many people writing that contemporary and open. There’s a lot of space to play in the music. Dino lets the personalities of the players come out as opposed to forcing them to play a certain way”.

Betti van der Noot’s voicings certainly are distinctive and so is the way he uses the flavoring of certain instruments such as the bass clarinet of Gianluigi Trovesi, Hugo Heredia’s alto flute, Sergio Fanni’s flugelhorn and Attilio Zanchi’s cello.

The nature of the improvisations and the conviction and joy with which the ensemble plays Betti van der Noot’s music, lets us know that all the musicians share the same feelings expressed by Egan and Gottlieb.

A real, artistic fusion is coming from Europe and Dino Betti van der Noot is one of the most important contributors.

Ira Gitler

Sorry – I’m Mine

Lyrics by Dino Betti van der Noot

Ladies and gentlemen, the show is on.

I will sing as beautifully,

as mightly as I can.

I think you’re going to applaud me

And give me bouquets of flowers.

Roses… roses…

for my singing, for my beauty,

my elegance.

And everyone will think he is my lord.

Sorry – I’m mine.

I share my art with you

But – sorry

I am a person

I’m only mine…

I’m mine.

My private life

is outside this club.

My heart belongs

to somebody I am in love with.

For whom I sing…

I sing.

Sorry

I know you’ll come to my dressing-room

eager to invite me

to invite me for dinner.

I’ll let you down

just saying thank you no.

Sorry – I’m mine.

I’m in love with someone

and that means

I’m not

Not really mine too.

I’m not mine at all…

at all.

Sorry

I know you’ll come to my dressing-room

eager to invite me

to invite me for dinner.

I’ll let you down

just saying thank you no.

Sorry – I’m not mine.

My art is part of my

love affair.

I’m so sorry

I’m not mine at all.

That’s why

I sing this way…

this way.

“Amo il ritmo – una delle ragioni per cui amo il jazz è il ritmo – ma ho passato qualche anno a liberarmi del ritmo”. Dino Betti van der Noot siede per la colazione all’Hotel Rosetta di Perugia. “Ho sperimentato con differenti metriche e infine ho scoperto che le più semplici sono perfette, se le utilizzi soltanto come… rotaie, guide”. In altre parole, la sensazione del tempo deve essere una guida, una presenza fisica, percepibile – “ma ad un certo punto, la musica – la melodia – deve realmente essere libera da questo tempo”.

È un concetto legato al titolo di questo album. È il problema di dare alla musica “la possibilità di danzare”. E la musica di Dino Betti van der Noot, in questa ulteriore fase del suo sviluppo, danza con grazia e logica, forza e delicatezza: grandiosi passi avanti in tutto il contesto. È probabilmente, nel jazz di oggi, l’approccio più tonificante e stimolante alla scrittura per grande formazione, che riprende la lezione del passato, elabora il presente, e aiuta a definire il futuro del linguaggio della big band.

Il passato? Come altri hanno sottolineato, Dino condivide con l’eredità ellingtoniana la passione di tagliare le sue composizioni su misura per i talenti individuali della sua orchestra. (Di fatto, questa è stata probabilmente la più vitale fra le realizzazioni artistiche di Ellington, dato che tanti pezzi duraturi – da The Mooche fino a Crescendo And Diminuendo in Blue – erano basati su questo concetto.) Quando Dino prepara un pezzo, crea una cornice per la particolare qualità del solista cui pensa – sia essa la forza agile di un Bill Evans, la passione controllata di un Mitchel Forman, o il grido rauco di una Carmen Lundy. Mentre spiega la sua facilità con una così ampia tavolozza di timbri strumentali, Dino si stringe nelle spalle: “Ho suonato molti strumenti nella mia vita – tutti piuttosto male”. (Tutti, io direi, eccetto uno.)

Attualmente, questo è il quarto album di Dino, ma può essere più accuratamente considerato il capitolo più recente di quello che è già un corpus ricco e notevole. Ovviamente, Dino si rivela in un’impressionante gamma di colori e di espressioni. Egli conduce programmaticamente i suoi ascoltatori attraverso deserti e al disopra di montagne; naviga su mari di gioia e di disperazione, evocando immagini visive taglienti e pure dalla sua ampia tavolozza di timbri. Ma malgrado il suo acume come pittore totale – e non fate sbagli, Dino è un diretto discendente di Ellington, via Thad Jones e Toshiko Akiyoshi, nella continua esplosione di possibilità timbriche – la freschezza del suo sound e l’originalità della sua musica in realtà sono altrove.

Specificamente, è la nascosta capacità progettuale, insieme con un notevole senso della scala e della forma, che connotano la scrittura di Dino. Egli lavora su ampie tele; ne ha bisogno, perché in larga parte si confronta con ampi problemi musicali (anche se riempie queste tele con dettagli fiinemente lavorati). La composizione che dà il titolo all’album fornisce l’esempio perfetto. Il suo lavoro più lungo – “È nato poco per volta al pianoforte”, dice Dino, che spesso si riferisce ai suoi pezzi in termini antropomorfici – A Chance for A Dance pone e risolve una varietà di problemi artistici. In esso, Dino è alle prese con equilibrio e struttura, tonalità che si intersecano, lo sviluppo simultaneo di una molteplicità di temi, e l’inserimento dell’individualità (il solista) nelle ora disciplinate, ora anarchiche costrizioni della società (l’orchestra). Riferendosi alle sue molteplici sezioni e al tema ricorrente, Dino ammette, “non mi ponevo problemi di struttura, ma sono soddisfatto della struttura che ho costruito. Penso che si debba avere un certo tipo di background classico per poter scegliere automaticamente questa struttura. Ogni tema porta all’inserimento di una diversa atmosfera”.

A questo punto di un saggio di questo tipo, chi scrive si sente generalmente obbligato a sottolineare che queste osservazioni tecniche non dovrebbero dissuadere l’ascoltatore musicalmente poco tecnico dal “tuffarsi” semplicemente e godersi la musica. Non insulterò la vostra intelligenza dicendo questo. Perché malgrado specifici pensieri analitici non debbano essere i compagni costanti di un ascoltatore o di un critico, essi sono abbastanza naturalmente ispirati dalla maggior parte della musica che vale la pena di ascoltare più di una volta. In effetti, tali preoccupazioni sono al centro del processo compositivo di Dino Betti van der Noot, e quindi non è sorprendente che la sua musica richieda reazioni sia intellettuali sia emotive.

Tranquillo e semplicemente elegante come persona, Dino è efficiente e diretto nella parola e nel pensiero; sono la sua prolifica produzione, e la sua costante attenzione al dettaglio, che rivelano la sua natura super-energica. E tuttavia, egli dice, “non mi sforzo. Se io fossi obbligato a fare musica, i risultati non sarebbero altrettanto buoni. Normalmente, non programmo neppure di fare un album. Esploro certe possibilità di fare musica, e quando ne ho a sufficienza incido un album”.

Il concerto che Dino ha dato a New York alla fine del 1987, dove ha diretto uno scelto gruppo di musicisti newyorchesi, è stato recensito molto favorevolmente sul New York Times: il critico, tuttavia, suggeriva che avrebbe potuto utilmente andare oltre al suo proprio materiale e utilizzare le sue capacità di arrangiatore su altre composizioni, dei compositori jazz riconosciuti come i maggiori. Non mi sorprende, data la sua ricerca per la perfezione, che Dino abbia attentamente considerato questo commento; ma ora, egli riflette, “non credo che cambierò alcunché. Perché in effetti, non arrangio; compongo”.

Per Dino, sono una sola cosa – medium e messaggio, sostanza e stile – ed è il successo di questa combinazione che, più di qualunque altra cosa, lo pone in una posizione a parte dagli altri compositori jazz del suo tempo.

Neil Tesser

Egan e Gotttlieb, due pilastri dell’orchestra di Gil Evans, hanno ambedue una grande considerazione per Betti van der Noot. “Trovo la musica di Dino molto sperimentale e stimolante”, dice Egan. “Sono felice di aver fatto l’esperienza di Gil Evans, perché così posso comunicare anche attraverso la musica di Dino. La musica di Dino è molto interessante per il basso. Mi è piaciuto anche suonare con gli altri musicisti dell’album”.

Gottlieb ha la sensazione che “la musica di Dino venga da una direzione che porta ad una comunicazione immediata. C’è l’influenza di Gil. È una scrittura interessante, unica, imprevedibile. Non c’è molta gente capace di scrivere in modo così contemporaneo e aperto. C’è un sacco di spazio per suonare in questa musica. Dino stimola ad esprimere la personalità degli esecutori invece di forzarli a suonare in un certo modo”.

Le orchestrazioni di Betti van der Noot sono certamente caratteristiche, e altrettanto si può dire del modo in cui utilizza il colore di certi strumenti, come il clarinetto basso di Gianluigi Trovesi, il flauto contralto di Hugo Heredia, il flicorno di Sergio Fanni e il violoncello di Attilio Zanchi.

La natura delle improvvisazioni e la convinzione e la gioia con cui l’insieme suona la musica di Betti van der Noot, ci fanno sapere che tutti i musicisti condividono gli stessi sentimenti espressi da Egan e Gottlieb.

Una vera fusione, artistica, viene dall’Europa e Dino Betti van der Noot ce ne offre uno dei più importanti contributi.

Ira Gitler